Kalmunai

Densely populated Kalmunai (3,383/km² in 2012) in the Ampara District is located below Batticaloa on the east coast of Sri Lanka (see red circle in map, Fig. 1). Located in the Dry agroecological zone (1750mm), Kalmunai has six administrative divisions: Periyaneelavenai, Natpiddimunai, Maruthamunai, Pandiruppu, Sainthamaruthu, and Kalmunai Central.

Livelihoods are dominated by trade, agriculture, and fishing. Drinking water is sourced from wells dug within a shallow aquifer on coastal sands. Rainfall infiltrates through sandy soils to collect into a ‘Gyben-Herzberg’ type groundwater lens where freshwater floats on denser brackish water. The Kalmunai coastline (Fig. 2) is of unequal width where Periyaneelavenai and Kalmunai Central are broader than Maruthamunai and Pandirripu. Brackish water lagoons intersperse the coastal wetland landscape below the shoreline.

Kalmunai was hugely impacted by the 2004 Tsunami (Fig. 3) when thousands lost their lives. Property, and livelihoods and drinking water wells were compromised. NSRC responded to this disaster by distributing drinking water, constructing toilets, engaging in homestead regenerative agriculture (Fig. 4), bioremediating contaminated well water (Fig. 5), and initiating domestic waste recycling.

NSRC also supported the livelihoods of hundreds of people in Kalmunai Central, Pandirippu, Maruthamunai and Periyaneelavenai. Beneficiaries from all these administrative divisions were mobilized into 34 community groups with 586 members (Fig. 6). All development work was planned and executed by these groups.

While these responses addressed prevailing issues, NSRC adopted a long-term approach to protect the Kalmunai coastline against extreme climatic events by establishing a 3 km coastal forest barrier or ‘bioshield’.

This proposition was first discussed with the groups to obtain their consent, identify areas for forest establishment and determine a strategy for their management. Discussions ensued with local government, Forest and Coast Conservation Departments, schools, and Hindu temples in the area to obtain approval and support for planting.

The closest natural coastal forest at Sanghamankanda (Fig. 7) was our reference for restoration since anecdotal information gathered from people of the area revealed that impacts of the Tsunami were almost negligible here.

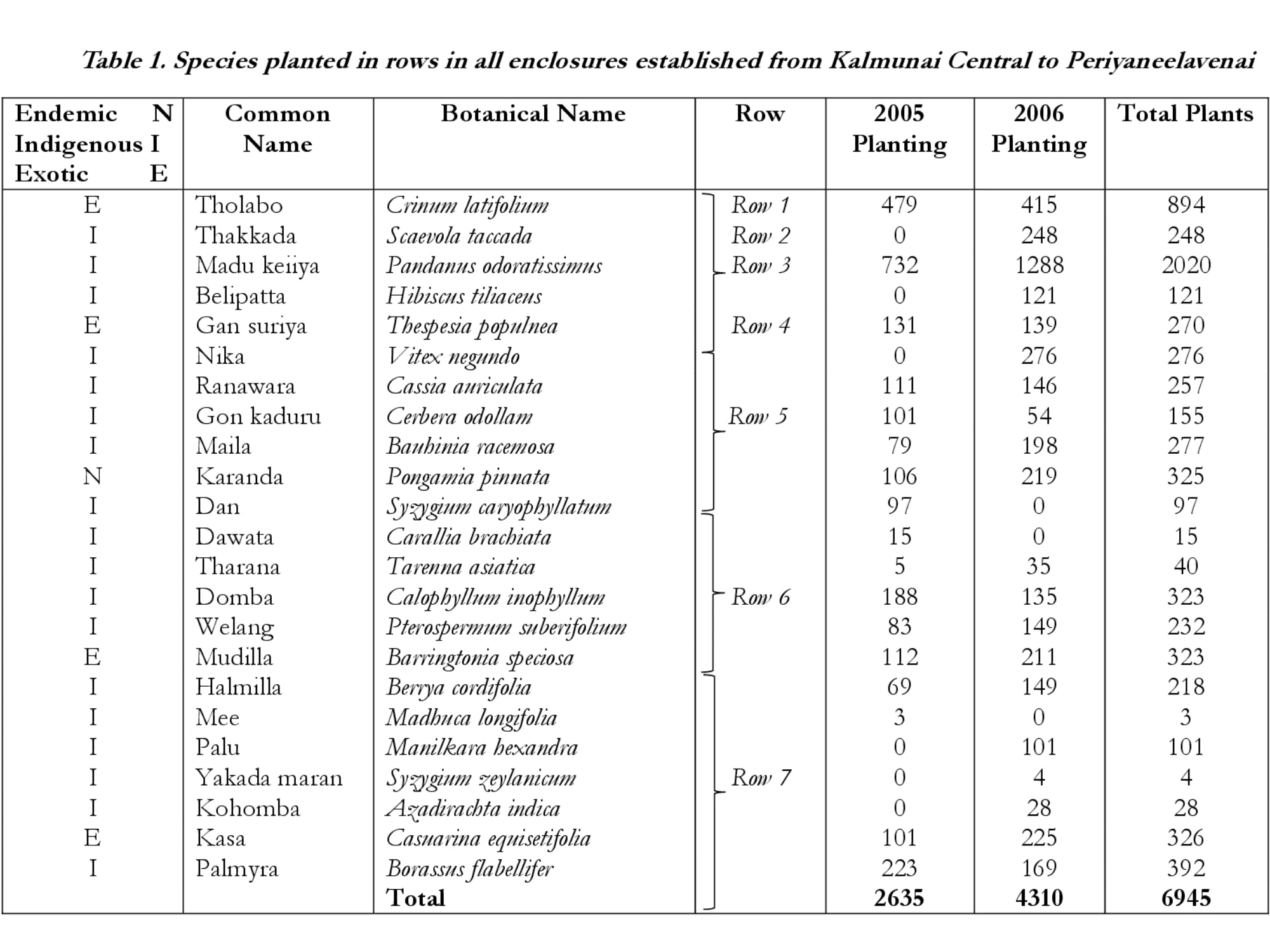

Investigations into its structure, composition and ecological function revealed that this Dry, Mixed, Evergreen Forest had four tree layers, no palms, or epiphytes. Of significance was the dense root mat of scrub vegetation below the tree line (Fig. 18) that protected against coastal erosion. Dominant tree species included Pterospermum suberifolium, Azadirachta indica, Manilkara hexandra, Cassia fistula and shrubs Cassia auriculata and Connarus monocarpus (Fig. 8). The landscape design of the bioshield was drawn using data collected from the Sanghamankanda forest. Plants were propagated at the NSRC nursery and purchased from the Forest Department.

Planting locations were identified along 3 km of the coast between Kalmunai Central and Periyaneelavenai. Seventy-five coconut cadjan-lined enclosures (Fig. 9) were constructed at specific sites along this tract after measuring the extent of sea intrusion at different times and locations. It was challenging to construct these enclosures in a sandy and windy terrain subject to storm surges (Fig. 10 as an inset in Fig. 9). Thereafter, water hyacinth was mixed with sand as a green manure and each enclosure mulched with paddy straw in preparation for plant establishment.

Several wells were dug in the sandy shore for water to irrigate plants. NSRC staff visited the bioshield frequently for maintenance up to 2009 and handed it over to the community to nurture thereafter.

The growth of the bioshield is shown at Periyaneelavenai across time in 2007 (Fig. 11), 2009 (Fig. 12) and 2024 (Fig. 13). In Pandirripu (Fig. 14), and Kalmunai (Fig. 15) in 2024.

Ecosystem services

In 2024 we observed that of all the species planted, Cerbera odollam, Carallia brachiata, Tarenna asiatica, Berrya cordifolia, Manilkara hexandra and Syzygium zeylanicum were absent and likely been felled for timber or fuelwood. Casuarina equisetifolia that was planted as a windbreak was phasing out with native shrubs such as Vitex negundo (Fig. 16) and Pandanus odoratissimus playing this function. Climax species including Syzygium caryophyllatum, Calophyllum inophyllum, Pterospermum suberifolium and Madhuca longifolia showed exceptional growth performance.

Of significance is that after 2009, despite the lack of maintenance (irrigation and fertiliser), plants fared well. Clearly, this native species dominated bioshield was resilient.

Several front row species including Vitex negundo (Fig. 17) and Pandanus odoratissimus withstood sea water intrusion and displayed great potential to counter sea level rise.

This ability, we reckon, is because the root mat of the bioshield (Fig. 18) is structurally similar to the dense root mat of the Sanghamankanda reference forest (Fig. 19) and may similarly be able to control erosion associated with sea level rise on the vulnerable Kalmunai coastline.

Densely planted trees and shrubs create barriers to flood inundation. The root mat formed could also bioremediate higher salinity levels in ground water (Fig. 20) that is the result of greater inundation of terrestrial land with sea water. This may already be occurring since Kalmunai was severely impacted by floods in 2023. Population expansion and rapid urbanisation has drastically reduced forest cover, which in 2020 extended over only 2.6% of the Kalmunai area. The drastic loss of forest cover results in habitat loss for biodiversity. In contrast, this floristically diverse bioshield across the Kalmunai shoreline offers habitat for biodiversity (Fig. 21).

Carbon sequestration is ongoing, both above and below-ground (Fig. 22). Increased soil organic matter stemming from increased leaf and stem litter creates habitat for soil biodiversity and facilitates natural regeneration. Moreover, shade created by tree canopies in the Kalmunai bioshield (Fig. 23) reduces heat stress and reduces loss of soil moisture. Heat stress has increased in Sri Lanka since 1997, with hot areas such as Kalmunai getting hotter and drier.

This valuable coastal forest bioshield has matured over the past 20 years because community members planned, planted, and managed it. It is now in danger from illicit felling, garbage dumping and urban expansion (Fig. 24) and requires protection.

A meeting of stakeholders who oversee the Kalmunai coastline was held on 6th March 2025 to discuss a conservation strategy for the Kalmunai bioshield. All stakeholders agreed that the bioshield must be conserved. The Coast Conservation Department stated that, although legislation was in place, it was difficult to catch miscreants because evidence mandatory for prosecution was unavailable. Law enforcement requires that informants in the community keep watch and speak out against poachers. The local administration called for sign boards to be erected in each division for awareness creation. Although these are important measures, we need to go further before it is too late. We need to formulate and implement national policy to conserve these bioshields immediately.

Even though the project at Kalmunai has ceased active operations, former staff including Yogeswari (Fig. 25) and Kumari (Fig. 26) continue to liaise with farmers and other members of the community groups. We value their continued support to our work.