Research

Our Goals, Approach, and Methods

Our goals are to enhance climate resilience, biodiversity conservation, water, and food security through land rehabilitation.

We initiated our research in the 1980’s on a small tea estate in the Uva Basin focusing on inventories of native species of flora and fauna in surrounding remnant forests, gathering seed and developing propagation techniques for native trees, and regenerative agriculture practices. We carried out survey research with villagers to identify species composition, structure and management approaches in village home and forest gardens. We also initiated a variety of comparative studies of biodiversity in native forests, plantation forests and village forest gardens. The theoretical synthesis of our learning was the analog forestry approach. By the mid 1990’s we began to work with farmers in various locations to apply the knowledge we had gained. Some of this work is described in the projects section of this website.

Our research is applied, focusing on watershed rehabilitation at the landscape and individual land holding scale.

Rather than going into villages with answers in hand, we meet with farmers/landowners to identify household issues, discuss aspirations for their land, and how they would benefit by adopting regenerative methods of land management (Fig. 1). In each community we develop demonstration models with farmers/landowners who are keen to invest their energy in land rehabilitation.

These demonstration models give an understanding of what can achieved across time when land rehabilitation is successful. Consequently, when neighboring farmers see the transformation in the demonstration model, they also seek to participate in land rehabilitation. This approach based on voluntary participation and mutual respect increases the pace and sustainability of our rehabilitation efforts as demonstrated in several communities across diverse agro-ecological zones in Sri Lanka.

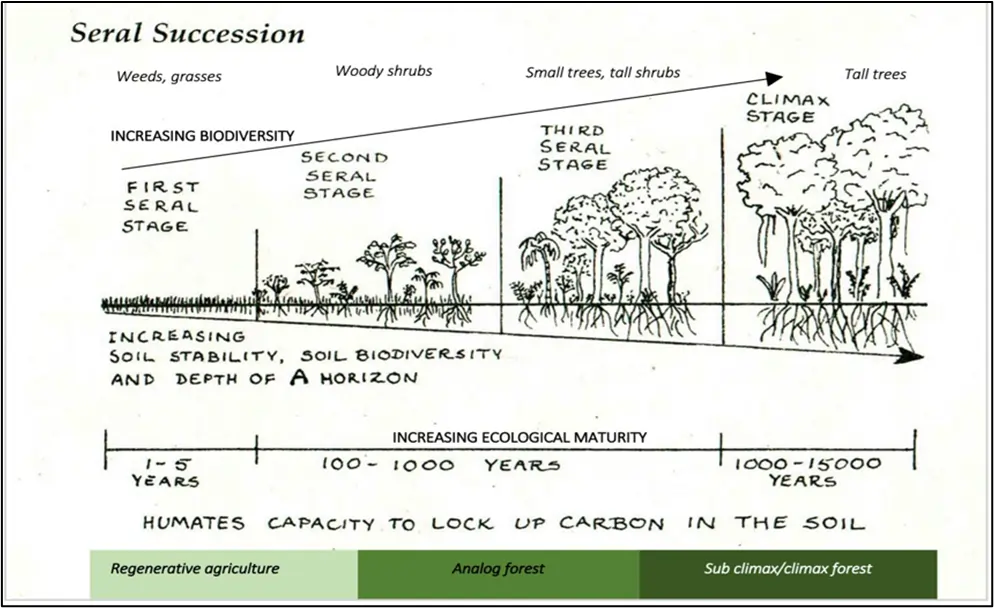

We align the land rehabilitation process in a farmer’s landholding with the phases of seral succession in forest development, Fig. 2.

Fig. 2: Analog forests are the continuum between agriculture and sub climax/climax forests in the successional process towards ecological maturity. Biodiversity and soil fertility increase with ecological maturity. At the inception with poor soil, high light conditions and no vegetation other than grass/weeds, farmers engage in regenerative agriculture. As the soil improves, seeds of shrubs and trees brought in by birds and animals or that were deliberately cultivated take root, and in time mature into an analog forest. In land under anthropogenic land management, this stage in seral succession can be arrested, or allowed to reach the sub-climax and climax stages of forest formation (Falls Brook Centre, 1997).

A farmer’s landholding is comprised of several different land uses in varying stages of ecological maturity. The ecological maturity of each land use determines the design for rehabilitation and methods used including regenerative agriculture, analog and conservation forestry, and bioremediation.

Regenerative Agriculture

To begin with, farmers may have poor soil, high light conditions and no vegetation other than grasses and weeds. We first engage in regenerative agriculture by planting annual (e.g., paddy, vegetables, green leafy vegetables, and cash crops such as maize) and semi perennial crops (e.g., pineapple, purple yam) for their subsistence, and income generation (Fig. 3). Soil conservation (e.g., contour drains if sloping land, hedgerows, mulching) and water management (small ponds, and canals) are foundation steps, and increasing soil fertility through the use of biological inputs (e.g., compost, biochar) is key (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). Regenerative agriculture ensures the rapid turnover of short-term income where risk is low owing to high crop diversity. Food and nutrition security is ensured because crop harvests occur through the year.

Analog Forestry

At the same time, farmers/landowners may convert other areas of their landholding to tree-dominated agriculture or forest gardens using analog forestry ( 6). This method of land rehabilitation combines data from the nearest climax or sub climax natural forest with farmers’ traditional knowledge to develop a multi strata, species rich, forest garden. Data gathered on the species composition, architectural structure, and ecological function of the native forest provides the matrix for the landscape design of the forest garden (Fig. 7). Here, marketable species that are analogous or similar to species from the natural forest: are planted in the same niches, provide similar ecological functions, and also generate income and other ecosystem services.

For example, in NSRC’s rehabilitated forest at Lemastota located in the lower montane, Intermediate zone (2500mm) in Sri Lanka, shade tolerant ginger (Zingiber officinale) is cultivated as a ground cover instead of the several Zingiber species found in the natural forests here. Cinnamon (Cinnamon verum) replaces Neolitsea fuscata in the lower, small tree layer since both are small trees from the Lauraceae family. Similarly, clove (Syzigium aromaticum) is used in the overstory instead of the native Syzigium assimile, while the native Michaelia champaca with high timber value emerges above the canopy of the forest. Black pepper (Piper nigrum) that is a lucrative crop replaces the wild pepper vine found in natural forests in this location.

By combining multiple layers of diverse long-term, perennial crops in space, forest gardens efficiently return investments made in the land across time. They ensure continuous and consistent food security because different trees are harvested at different times. For example, a jak tree will produce fruit for 40 years while a coconut tree remains productive for over 60 years. Moreover, a high diversity of crop and native tree species creates habitat for biodiversity, enhances hydrological potential (increased leaf litter increases soil moisture, improves percolation into the ground water table, and enhances base flow), increases economic productivity, and ensures climate resilience.

Conservation Forestry

We engage in conservation forestry in areas where landholdings border natural forests or streams, or in wetland areas (Fig. 8 and Fig.9). By using species native to the original forests, we extend the reach of the natural forest, and create corridors for biodiversity movements across the landscape mosaic.

Bioremediation

While vegetation establishment in areas under analog and conservation forestry will improve ground water potential, the root mat created by native species of trees, shrubs, and other plants in densely planted areas around wells and in the riparian zone of streams, will stabilise banks, reduce erosion, filter pollutants, provide habitat for aquatic biodiversity and significantly improve water quality quality (Fig 10 and Fig. 11).

The following similar processes are applied when implementing these methods:

- All components of the landscape mosaic in the watershed are mapped including remnant natural forests, degraded common lands, streams, and riparian areas, making possible catchment basin planning.

- Inventories are made of existing vegetation at each contour if this is a mountainous area, including native flora and fauna.

- Natural forests are surveyed with respect to their vegetation structure, composition, and the ecological functions they provide.

- Individual farms are mapped to include their physical characteristics, vegetation and biodiversity observed in distinct land use areas. This enables an assessment of their ecological maturity.

- A landscape design is created in collaboration with farmers/landowners for each land use area requiring rehabilitation. Annual and perennial crops are used in production areas of the landholding while native species are used as fencing, in riparian and buffer zones.

- Nurseries are established to propagate planting materials.

- Planting is carried out with farmers during the rainy season

Once a project is initiated, NSRC facilitators live in villages working daily with farmers until management techniques are mastered. Trained to create and manage nurseries, design watershed rehabilitation, and teach organic farming methods, the facilitators also aid farmers in keeping records of yields, inputs, and sales, thus increasing farmers’ understanding of improvements in incomes and ensuring that the management methods they employ serve them well.

While household food security and environmental resilience are first priorities, developing market opportunities for high value crops is an integral part of the NSRC extension outreach.